IBM has built a computational

creativity machine that creates entirely new and useful stuff from its

knowledge of existing stuff. But can computers be creative? That’s a question

likely to generate controversial answers. It also raises and some important

issues too, like how to define creativity. Seemingly unafraid of the

controversy, IBM has darted into the fray by answering this poser with a

resounding ‘yes’. Computers can be creative, they say, and to prove it they

have built a computational creativity machine that produces results that a

knowledgeable human would consider novel, useful and even valuable—the

hallmarks of genuine creativity. IBM’s chosen field for this endeavour is

cooking. The company’s creativity machine produces recipes based on chosen

ingredients or cooking styles. And they’ve asked professional chefs to evaluate

the results and say the feedback is promising. Computational machines have

evolved a great deal since they were first used in war for code-cracking and

gun-aiming and in business for storing, tabulating and processing data. But it

has taken some time for these machines to match man human capabilities. In

1997, for instance, IBM’s Deep Blue machine used deductive reasoning to beat

the world chess champion for the first time. It’s successor, a computer called

Watson, went a step further in 2011 by applying inductive reasoning to huge

datasets to beat humans experts on the TV game show, Jeopardy!.

Their first problem of course is

to define creativity. The choice of problem, to create new recipes, is clearly

a human decision. The team has then gathered information by downloading a large

corpus of recipes that include dishes from all over the world that use a wide

variety ingredients, combinations of flavours, serving suggestions and so on. They

also download related information such as descriptions of regional cuisines

from Wikipedia, the concentration of flavour ingredients in different

foodstuffs from the ‘Volatile Compounds in Food’ database and Fenaroli’s

Handbook of Flavor Ingredients. So big data lies at the heart of this approach.

They then develop a method for combining ingredients in ways that have never

been attempted using a ‘novelty algorithm’ that determines how surprising the

resulting recipe will appear to an expert observer. This relies on factors such

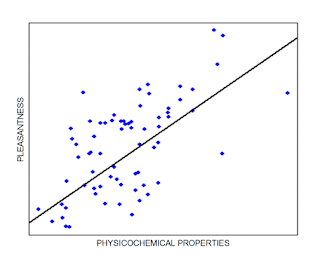

as ‘flavour pleasantness’. The computer assesses this using a training set of

flavours that people find pleasant as well as the molecular properties of the

food that produce these flavours such as its surface area, heavy atom count,

complexity, rotatable bond count, hydrogen bond acceptor count and so on. The

last stage is an interface that allows a human expert to enter some starting

ingredients such as pork belly or salmon fillet and perhaps a choice of cuisine.

The computer generates a number of novel dishes, explaining its reasoning for

each. Of these, the expert chooses one and then makes it.

More information: